Domestic Sewing Machine Company History

The following is a summary of information I have collected about the Domestic Sewing Machine Company history. It comes from

a variety of sources, including advertisements, newspaper articles, trade magazine articles, business directories,

books and court cases.

There is some conflicting information and I have noted where I had to resort to speculation. I would be pleased to

hear from anyone who has additional documented information.

Shortcuts

1860 - 1869 The Early Years

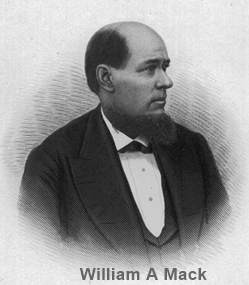

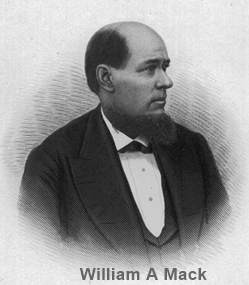

William A Mack

began manufacturing parts for sewing machines in Seville, Ohio in

1860 .

William A Mack

began manufacturing parts for sewing machines in Seville, Ohio in

1860 .

In 1863

and 1864,

Mack patented improvements to sewing machine design and began manufacturing complete machines, which he

sold under the name “Domestic Sewing Machine”. He built the first batch of 12 machines by himself and they were reported

to be not very attractive, but they performed well enough to attract attention.

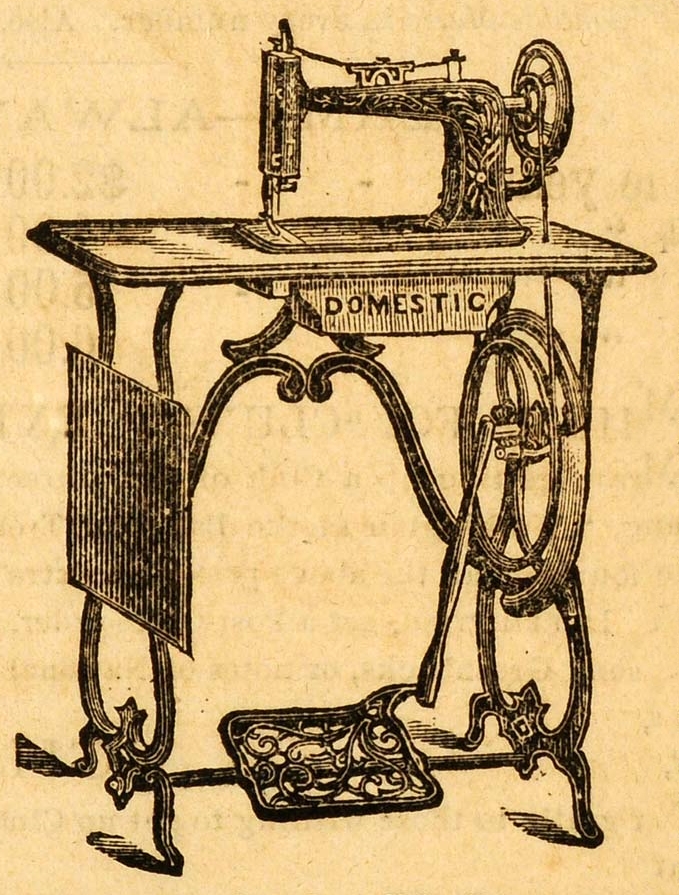

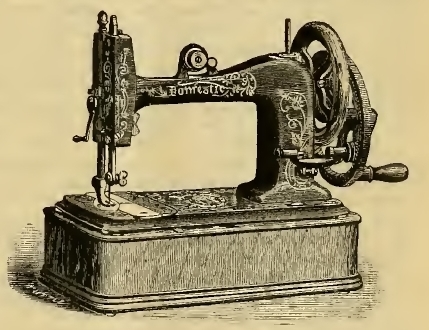

Mack’s design was the first high arm sewing machine. Considering that the main competitors at the time were Singer’s

Model 12 (transverse boat shuttle), Wheeler and Wilson’s No 1-4 (rotary hook with very thin bobbins, curved needle),

Grover and Baker’s Double Chain Stitch (curved needle, very low arm), and Howe’s Model A (reciprocating boat shuttle), it was quite

an improvement in sewing space and bobbin capacity.

Mack began using the business name

Domestic Sewing Machine Company as early as 1864.

Some respected sources state the business

name as Wm A Mack & Co. The only reference

I could find in newspapers under that name was a

shoe factory in 1875 in Norwalk, OH. This

obituary

states that Mack did have a shoe factory in Norwalk for some time.

I could not find Wm A Mack & Co in any business directories.

During these early years, Mack sought out investors to help with production costs and after making machines on his own,

he contracted out manufacturing. By 1864, his machine was being manufactured and sold by

G. W. Crowell & Co of

Cleveland, OH. G. W. Crowell ads stated that it was warranted to do the work of all other machines currently on the market.

In 1864, Mack moved to Norwalk and began building machines at the

N S C Perkins Shop on Whittlesey Avenue. Perkins

licensed and manufactured sewing machines and attachments.

He made the Gardiner and the Moore, the latter was

reported to be so popular that the larger manufacturers crushed its

production. The timing was right in 1864 when W A Mack approched Perkins with his Domestic machine designs and they

had a successful partnership for several years manufacturing Domestic machines in the "Perkins Shop". After Domestic

production moved elsewhere, Perkins manufactured the

Dauntless

sewing machine for a few years.

By 1866, there were many advertisements for sales agents in newspapers around the country.

The machine was claimed to be

suitable for harness, boot and shoe making as well as household sewing and could be used to hem, tuck, gather and braid.

They stated it was the only sewing machine with a hardened cast steel shuttle.

An 1868 ad claimed that “the heaviest leather and the most delicate fabrics can be sewed with the same needle if desired”.

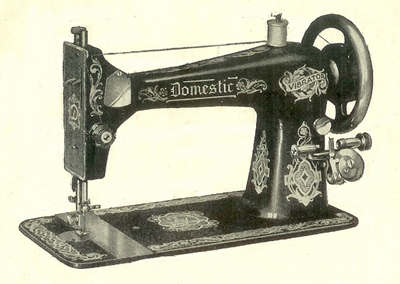

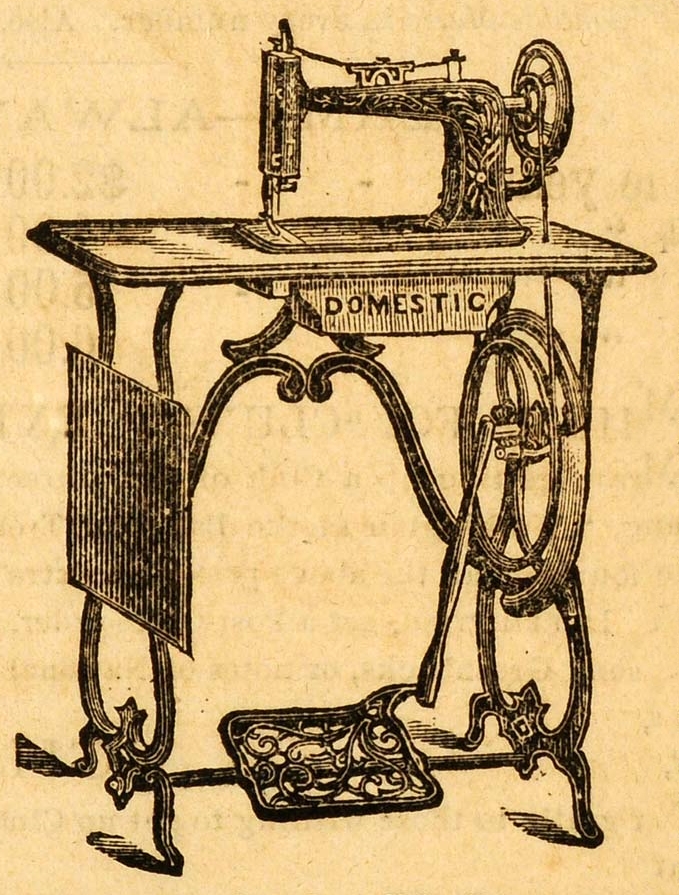

That sounds like quite a machine! Unfortunately, they are extremely rare. The only photo I have ever seen of the 1860s

machine is in Carter Bays book, The Encyclopedia of Early American and Antique Sewing Machines, 2nd edition. It is not

in the 3rd edition. It looks very similar to the later rectangular base high arm machine.

We know that they had a wheel feed, which was shown in the 1863 and 1864 patent diagrams.

Mack was sued for patent infringement

for the wheel feed and other features in 1866 and a ruling was finally made in July, 1868. Complainants were

members of the Sewing Machine Combination (AKA Sewing Machine Trust): Orlando Potter,

Nathaniel Wheeler, Wheeler & Wilson SMCo, Grover & Baker SMCo, and Singer SMCo. The last member in the Combination,

Elias Howe, was not mentioned in the article, possibly because his patent had expired in 1867.

Judge Sherman of the US Court, Northern District of Ohio ruled that the Domestic Wheel Sewing Machine, manufactured

at Norwalk Ohio, was an infringement of the 1856 Allen B Wilson patent. The judge ordered that Mack reimburse the

complainants for the profits, gains, and advantages he received from the infringement. A perpetual injunction was

issued against Mack from further infringement.

Apparently a licensing agreement was reached, because a few months later

newspaper ads described the machine’s features

and stated it was improved and now fully licensed. Touted features included: it can sew a wide range of work as well as

three sizes of competitor’s machines, thread thickness can be changed without adjusting tension, working parts can never

get out of time and never need adjusting, ease of operation, quiet, simplicity, cases of inlaid wood, and frames

ornamented with carved medallions. Some ads said it was “Improved” but there is no indication what was changed in

the design.

William’s brother Frank Mack began selling the Domestic machines by wagon in 1866. In 1867, Frank became the general

selling agent for the company and continued in that role for several years. In 1872, Frank left the company to form Mack

Brothers with his brother Miles.

Click here

for more information about Frank Mack, William A Mack, Mack Brothers,

and the start of the Standard Sewing Machine Company.

The Domestic Sewing Machine Company of Norwalk, OH filed for a

certificate of incorporation on December 24, 1868,

with $100,000 capital in shares of $500 each. The corporators were W A Mack, N S Perkins, F Mack, M P Smith and James H

Perkins.

In 1870, the Domestic factory in Norwalk, OH employed

80 men working 10 hrs a day. They were paid an average of $2.75.

Ads proclaimed

that the “Improved Domestic” was best due to its simplicity, ease of use, ability to sew everything from

fine fabrics to leather, and durability. It was also “fully warranted” for an unspecified amount of time. In 1870, some

ads mentioned “drop feed”, so they had moved on from the wheel feed by then.

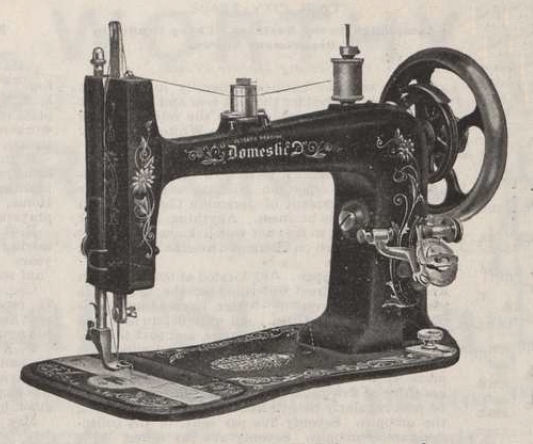

1870 – 1893 Domestic Sewing Machine Company – The Blake Years

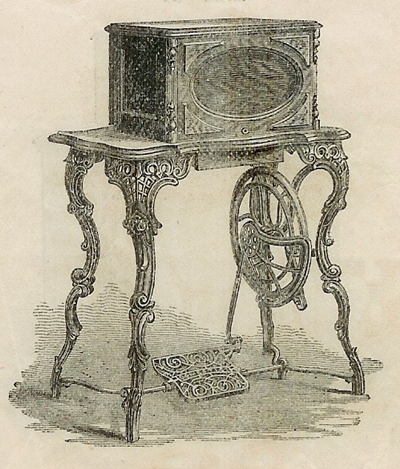

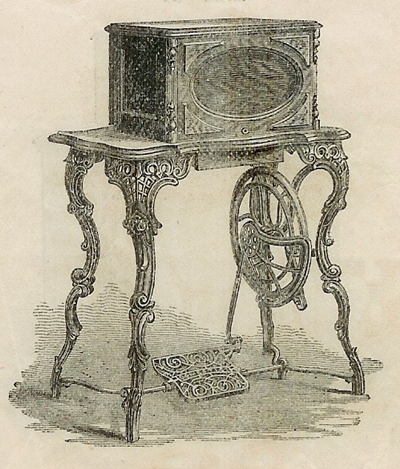

Meanwhile, in Scranton, PA, the firm of

George Blake & Co were agents for the Domestic sewing machine.

The “& Co” was George’s brother James, who had

patented a sewing machine table with a drop

leaf in 1869. In 1870, they advertised the Domestic sewing machine with the Blake’s patent auxiliary table, which was

claimed to more than double the space for supporting work. The ads stated that the Domestic was from “the West” (Ohio!)

where it was fully tested and widely popular. The ads also sought sale agents for Domestic and some said to write to the

DSMCo at a Scranton lockbox.

James reportedly brought the idea of investing in the Domestic to the attention of his brothers.

At some point, George and James, along with their brothers David, Eli and Robert, bought the Domestic Sewing Machine

Company. According to an

anecdote

in the Sewing

Machine Times, the Blakes beat out another potential investor by one day. It is not clear exactly when that happened.

Articles in the Sewing Machine Times make it sound like

the Blakes formed the company in the early 1870s and moved

operations to New York, but clearly the company was already incorporated and manufacturing machines on a commercial

scale before the Blakes got involved. Some sources say that the company was incorporated in 1870, so perhaps that is when the

Blakes took over and vastly expanded the business.

William A Mack was an inventor, and he was likely glad to find someone else to provide capital and run the business

end of things. Mack patented numerous inventions throughout his career and reportedly did all of the experimental and

constuction work himself rather than employing mechanical assistants. He was also one of the first to recognize the

importance of attachments for household machines. He stayed with the company until 1884, when he

and his brother Frank left to form the Standard Sewing Machine Company. There he was instrumental in the development

of the Standard Rotary sewing machine.

The Blake brothers were involved in the company in various ways.

David Blake was president for the first 7 years, then vice-president. George Blake was vice-president from 1870-1877,

then secretary. James was secretary of the company for several years. Robert and James patented several of the inventions

that were used in the machines. Eli seems to have been the money man at first, but he was company president from 1877-1890.

Cousin James Woodruff “JW” Blake was the general

manager of the executive offices for about 15 years, up to 1893.

This claim in a lawsuit states that William A Mack

organized a corporation called the Domestic Sewing Machine Company on November 5, 1870. Since the company had already filed

for incorporation almost 2 years earlier, again, perhaps this is the date control was passed to the Blakes.

By March of 1871, the company headquarters had moved to Toledo, OH

and they had contracted with Providence Tool

Company to manufacture 100,000 machines at a cost of $16 each. This work was done under the supervision of

Cyrus B True.

Initial production was reported to be 600 machines per week. There were apparently rumors that that Domestic could not

meet the orders because they placed a “To Whom It May Concern”

notice in the newspaper stating that they “have enlarged

their capital and manufacturing facilities, and are supplying the increasing demand for their Celebrated machines

faster than ever, all the miserable lies of interested parties to the contrary notwithstanding”.

By March of 1871, the company headquarters had moved to Toledo, OH

and they had contracted with Providence Tool

Company to manufacture 100,000 machines at a cost of $16 each. This work was done under the supervision of

Cyrus B True.

Initial production was reported to be 600 machines per week. There were apparently rumors that that Domestic could not

meet the orders because they placed a “To Whom It May Concern”

notice in the newspaper stating that they “have enlarged

their capital and manufacturing facilities, and are supplying the increasing demand for their Celebrated machines

faster than ever, all the miserable lies of interested parties to the contrary notwithstanding”.

I have not found anything to indicate where cabinets were made while the machines were being manufactured at PTC.

On April 8, 1871, Mack applied to register the name “Domestic” as a

trademark for the company. The application was

granted on August 1, 1871. By this time he also sold attachments, including a “ruffler, pleater, braider, gatherer,

tucker, embroiderer, quilter, button-hole adjustable table and other sewing-machine attachments.” They also sold

needles, silk, thread, oil bottles and other goods.

In the trademark application, Mack stated that the business was being reorganized and that machines would thereafter

be manufactured by the new company. The application was witnessed by George and David Blake, two of the new investors.

David Blake is listed as company president in a

trademark application

in November of 1871. The Domestic Sewing Machine Company is listed in the

1871-72 New York City Directory. It is not listed in the 1870-71 Directory.

To complicate matters further, in the book

From the American System to Mass Production, author David Hounshell

states that it was actually Singer who formed the DSMCo. He says that Singer wanted to compete in the lower priced

market, but felt that a lower priced Singer would hurt the sales of their brand name. To get around this,

they formed the DSMCo, and while not directly owning it, they controlled the company. They acted as a middleman between

manufacturing and sales and took $3 from the sale of every machine. He says it was Singer who contracted with

Providence Tool Company to manufacture Domestic Machines. The book references cite several letters found in the

Singer archives between Domestic, Singer, and PTC about this contract. Some of the letters

were to or from "D Blake" of DSMCo. There were disputes between Domestic and PTC about the workmanship and uniformity

of the product,

and Singer eventually canceled the contract in mid-1873. The book says that Singer and DSMCo then set up the

Domestic Manufacturing Company to make Domestic machines starting in 1874. DMCo began manufacturing using special

machines, tools and gauges bought from PTC in 1873. The book does not say when the association of the companies ended.

We will see later that

court records

from a lawsuit in 1897 say the Domestic Manufacturing Company was actually formed in 1881, not 1874.

As with the claims that the Blakes started the company, we know

that W A Mack and colleagues incorporated DSMCo in 1868 after using that company name for 4 years. So,

there are conflicts between other sources

and the Hounshell book. It is not clear how Singer got involved. Did Singer invest in Domestic before, with, or

after the Blakes? Why would the Blakes have wanted Singer to be involved at all? Why is the Singer connection not

mentioned in the company history in any other sources that I found, including lawsuits?

The early 1870s will remain murky until more information is uncovered. In any event, if Singer did help the DSMCo

expand, in retrospect it seems like it was not a good move to help create a future competitor.

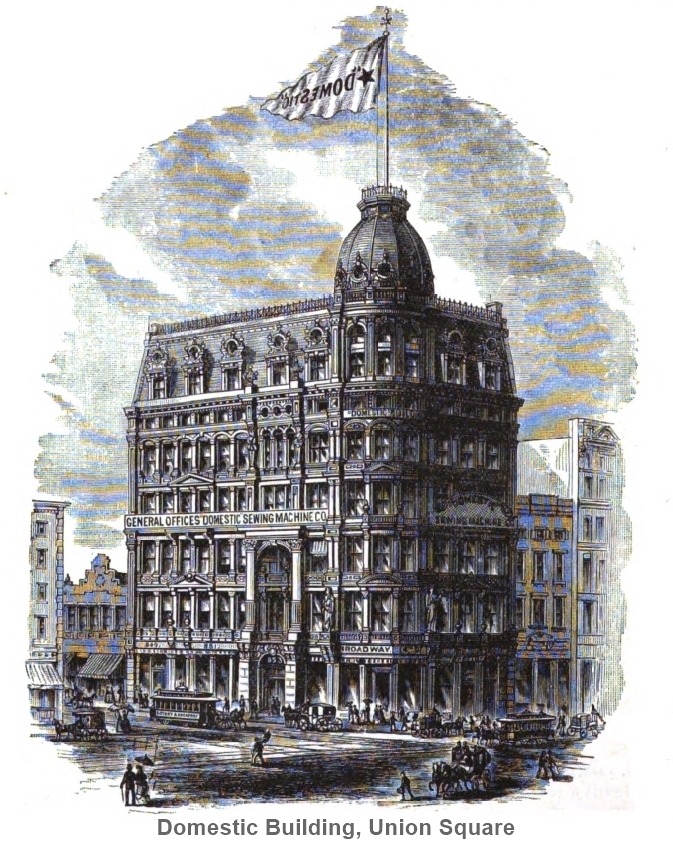

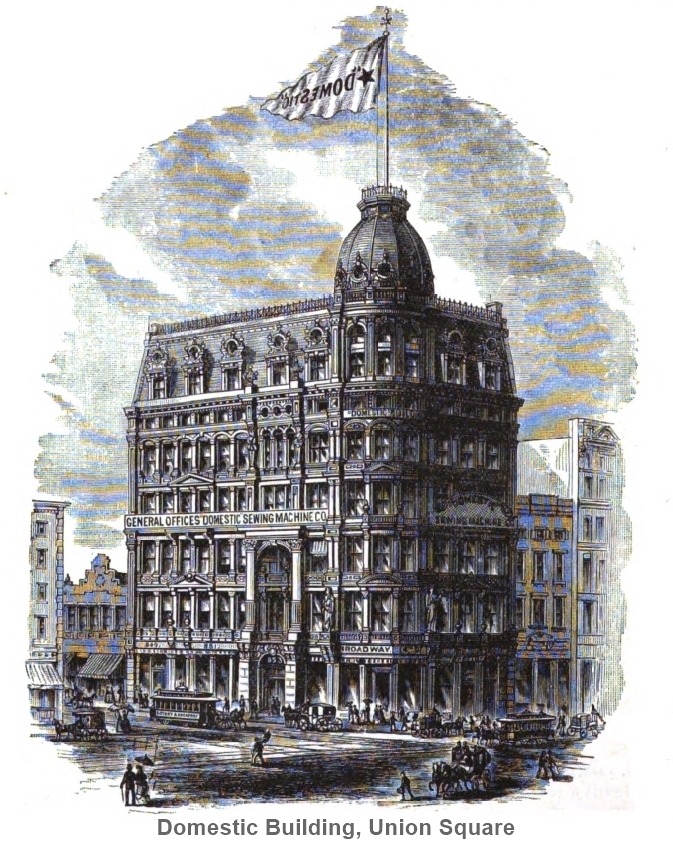

The Blakes moved the company headquarters from Toledo to 96 Chambers Street in New York, NY and proceeded to build a

grandiose building to house the company. They chose the site of the

Cornelius Roosevelt estate at the corner of 14th

and Broadway, as well as part of a neighboring lot, and leased the land for $20K/yr. They tore down the historic

mansion to build an 8 story ornate cast iron building that dwarfed everything in the vicinity at a cost of over $250K,

some sources say $300K. The building was to be returned to the property owner at the end of the 21 year lease.

The Blakes moved the company headquarters from Toledo to 96 Chambers Street in New York, NY and proceeded to build a

grandiose building to house the company. They chose the site of the

Cornelius Roosevelt estate at the corner of 14th

and Broadway, as well as part of a neighboring lot, and leased the land for $20K/yr. They tore down the historic

mansion to build an 8 story ornate cast iron building that dwarfed everything in the vicinity at a cost of over $250K,

some sources say $300K. The building was to be returned to the property owner at the end of the 21 year lease.

They expected to occupy the building in November of 1872 , but the open house to reveal the business to the public

did not happen until June of 1873. The open house

was an elaborate affair that attracted thousands of visitors. There were a number of displays, including a

Domestic machine run with a steam engine using No 20 cotton instead of a leather belt. Many visitors rode the elevator

to view the city from the rotunda. It was reported that several hundred people were employed in the building.

The Blakes added a line of paper patterns

to their product line by May of 1873. The pattern business occupied the second floor of the new building. They also

started publishing The Domestic Monthly, a

fashion magazine featuring their patterns, sometime in 1873.

Also in 1873, DSMCo

searched for a location to build their own factory. Coincidentally one of the candidates was

Norwalk, CT. The company location requirements were ready access to New York, and a healthful and attractive location

with thrifty

people, houses and cheap land. They claimed they would employ 2000 workers, which would increase the population

by at least 5000 people. In the end, the company chose Newark, NJ and their first

factory was the corner of Orange

and High Streets.

The extravagent expenditure on the Domestic building was ill advised for the new company, and when the Panic of 1873 hit,

they ended up in financial trouble .

They advertised to rent out most of the space in the building. They laid off 225 workers

in Newark, where they were building their new factory.

In November of 1873, "irregularities"

were reported at the Mercantile Bank, where Eli Blake was president. Eli was a principal

stockholder in the DSMCo as well as brother of DSMCo president David Blake, and had advanced DMCo large sums of money

without knowledge of the other directors. It was reported that he had also loaned money to himself and others, and the

money had not been paid back due to the panic. The bank examiner got involved and Blake resigned from the bank. Later

reports stated that the DSMCo financial issues were due to stringency in the money market and that they had assets is

excess of $1 million over their liabilities. One report stated that the new building was already paid for.

April 1874, DSMCo resumed operations

after being closed in “the panic”. A news report said that manufacturing had

previously been done in Providence, RI, but in the future it will be done at the new factory in Newark, NJ.

Steven A Davis was assigned the task of modernizing the sewing machine design and setting up the new factory in Newark

to manufacture it. He worked for the company for decades, working his way up to Foreman, then Assistent Superintendent, then

Superintendent of the factory in 1888. He patented many

design improvements over the years and several models were referred to as his inventions. Reminiscing with the SMT,

Davis stated that the first factory began in one

20 foot square room and he was the first mechanic. The business increased rapidly eventually the iron works alone

employed 1200 men and turned out 400 machines a day.

DSMCo bought the Grover and Baker Sewing Machine Company in

1875 or 1876.

I don't have any other details on this.

In 1880, the Newark factory was

moved

to larger facilities at the corner of Warren and High streets, where it remained until the

company moved out of Newark.

Before 1881, DSMCo owned property in Newark, but the firm of James R Blake & Co leased it and manufactured the machines

under contract with the company. Other departments doing other work were run by different people. In 1881, the board

decided to increase the

facilities and consolidate operations under one management organization for greater efficiency.

To accomplish this, the Domestic

Manufacturing Company was founded on May 3, 1881. Officers were Eli Blake, John Dane, Jr, Robert Blake and

James Blake (4 of the 5 directors of DSMCo).

In 1880, the Newark factory was

moved

to larger facilities at the corner of Warren and High streets, where it remained until the

company moved out of Newark.

Before 1881, DSMCo owned property in Newark, but the firm of James R Blake & Co leased it and manufactured the machines

under contract with the company. Other departments doing other work were run by different people. In 1881, the board

decided to increase the

facilities and consolidate operations under one management organization for greater efficiency.

To accomplish this, the Domestic

Manufacturing Company was founded on May 3, 1881. Officers were Eli Blake, John Dane, Jr, Robert Blake and

James Blake (4 of the 5 directors of DSMCo).

Early in 1890, production was down and there were

rumors of dissension among the board of directors. Later that year, there was a contentious

board meeting that resulted in a

management change . President Eli Blake and Secretary

James Blake, plus the Treasurer were ousted. David Blake was elected Treasurer and George Blake (former VP) was elected

Assistant Treasurer and Secretary. It appears there was significant conflict between the brothers.

Even though the company business offices had moved to New York in 1871, the DSMCo remained incorporated in Ohio. In 1891,

management announced that it was inconvenient to conform to technicalities there and would be advantageous to combine

their business and manufacturing operations under the laws of one state. On April 3, 1891, the

United Domestic Sewing Machine Company

was organized in New Jersey. The plan was to acquire all the property, assets and liabilities of the

DSMCo of Cleveland, OH. There was no change in the business or management, and they continued to do business under the

name DSMCo. The Blakes were still involved at this point, with David Blake as vice-president and George Blake as Secretary.

In 1892, the extravagant Domestic Building reverted to the landowners as specified in the lease.

In May through October of 1893, DSMCo had an exhibit

at the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago. The SMT described their

display as one of the neatest and most artistic in the immense Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building. It consisted

of two rooms with lavish decorations, including and embossed star on the ceiling lighted with electricity. There were

displays of elaborate needlework done on DSMs. Of course, there were sewing machines being demonstrated, and the

chain stitch looper and button-hole worker were featured. They won

awards for “Family Sewing Machine” and “Sewing

Machine Work”.

From 1893-1895 there were numerous newspaper reports of a Sewing Machine Combine involving several of the major

sewing machine manufacturers, including Domestic. It never came to pass, but there were apparently a lot of rumors about it.

Click here for more details about the Sewing Machine Combine

that didn't happen.

1893-1899 The Receiver Years

On May 19, 1893, two attachments

were placed on DSMCo based on suits placed by Astor Place Bank in NY. On

May 23, 1893,

executive offices of DSMCo were suddenly

moved from 853 Broadway, New York to Newark, NJ.

The company claimed they had been contemplating the move for some time due to

excessive taxation and legal disadvantages of being a foreign corporation.

The announcement said that only a branch office would be maintained in NY.

On May 19, 1893, two attachments

were placed on DSMCo based on suits placed by Astor Place Bank in NY. On

May 23, 1893,

executive offices of DSMCo were suddenly

moved from 853 Broadway, New York to Newark, NJ.

The company claimed they had been contemplating the move for some time due to

excessive taxation and legal disadvantages of being a foreign corporation.

The announcement said that only a branch office would be maintained in NY.

The company was forced to declare

insolvency .

On June 2, 1893, Judge Andrew Kirkpatrick

was appointed receiver

of the Domestic Sewing Machine Company

and on June 6

he shut down all company operations

in Newark, throwing 700 employees out of work. It was expected that the shutdown

would be of short duration. On June 20th, Judge Kirkpatrick issued a statement about the

company finances.

On June 24, 1893, Judge Kirkpatrick was granted power to resume operations, and on June 26, the

factory reopened and began producing

150-200 machines per day with about two thirds of the usual workforce. Machines were sold

for cash to pay for production expenses. The plan was to find new capital to get the

business going again.

Although ownership of the Domestic Building reverted to the Roosevelt estate at the end of the lease in 1892, some

elements of the DSMCo remained in the building as tenants. In late February of 1894, the new owners

announced drastic rent increases and the remaining

departments, including the Domestic Fashion Company, had to hastily find

new offices . They moved a

short distance down 14th street before March 1.

For the next few years, there were

news reports that the factory was busy and

the receivership was going well.

Eventually, Judge Kirkpatrick was successful in bringing the Domestic Sewing Machine Company back to solvency.

On April 1, Judge

Kirkpatrick was authorized to sell

the DSMCo and Domestic Mfg Co. The sale ended the receivership. The Domestic Manufacturing Company had been

operating since 1893 and

the DSMCo was not involved with sales. Six secured creditor banks bought the company and unsecured creditors

and owners of preferred and common stock got nothing.

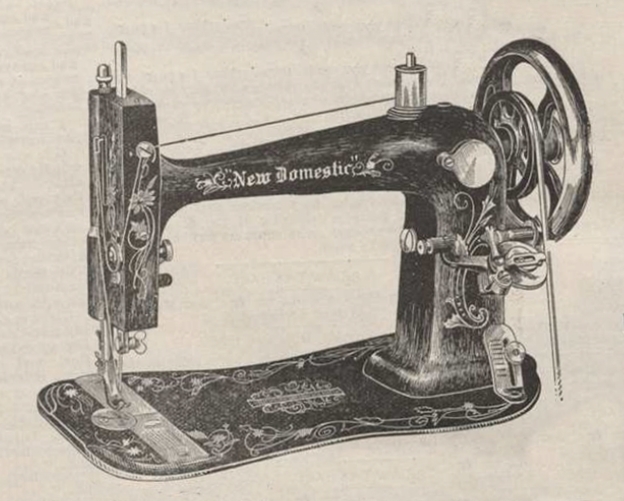

1899-1903 New Domestic Sewing Machine Company Years

In April of 1899, the new owners incorporated the

New Domestic SMCo in NJ. The new company

acquired both the Domestic Sewing Machine Company and the Domestic Manufacturing Company.

The new management promptly began

updating and improving the factory and planning new products.

Stephen A Davis was still the superintendent.

In September, the business and executive offices were

moved back to New York

and housed together with the export offices for greater efficiency. An

advertisement

that month listed 28 countries that Domestic machines were exported to. In April of the next year

they moved again into a bigger office space.

The new management promptly began

updating and improving the factory and planning new products.

Stephen A Davis was still the superintendent.

In September, the business and executive offices were

moved back to New York

and housed together with the export offices for greater efficiency. An

advertisement

that month listed 28 countries that Domestic machines were exported to. In April of the next year

they moved again into a bigger office space.

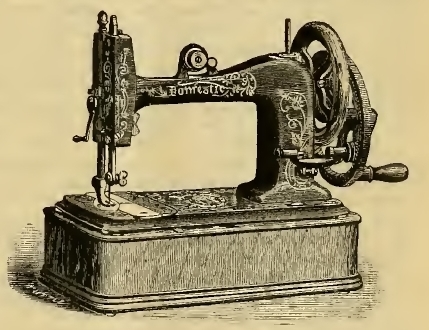

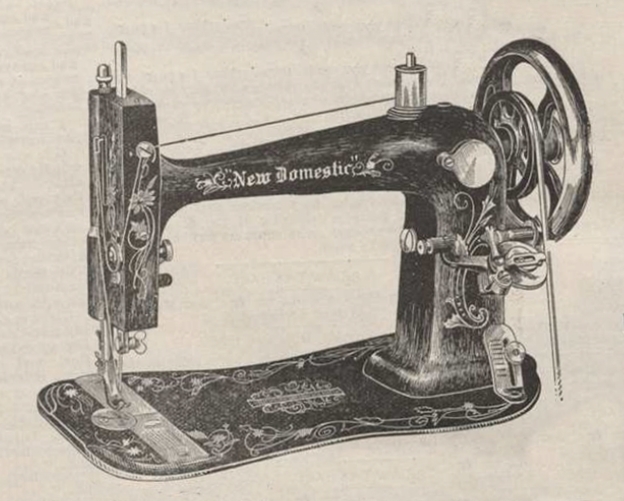

In 1901, Domestic had an exhibit at the

Pan Am exhibition

in Buffalo. NY. They had a good location at the corner

of two aisles and aggressive sales people. The booth featured the recently introduced

New Domestic model with its

chain stitch looper and 5 stitch ruffler attachment. The New Domestic won a

gold medal

for “Best Family Sewing Machine”.

In March of 1901, it was reported that George Todd

had replaced Stephan S Davis as Superintendent.

At this time, the factory was running full time, and management was reported to be advanced and progressive.

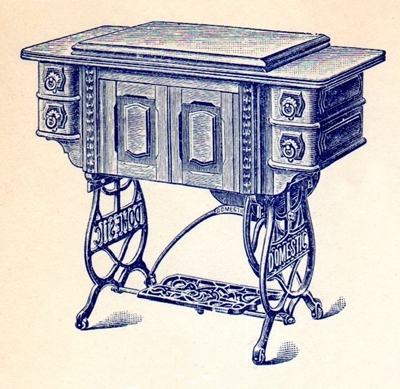

Domestic was one of the few companies at that time to make their own cabinets and they made their own machines

starting from raw materials.

1903-1910 The Domestic Sewing Machine Company, Again

On January 23, 1903, the New Domestic SMCo was sold to the

Domestic Sewing Machine Co.

of Newark, NJ. The company headquarters was moved back to Newark.

The article stated that the

purpose of NDSMCo was to reorganize the company for the purposes of sale and that this was the plan since the

receivership and that this “clears the business from all the embarrassments of the earlier concerns”. The work of the

NDSMCo modernizing the factory was successful and the new company had plans for expansion to increase production and

a new power plant. Manufacturing operations would continue without pause. The factory was reported to be a model of

efficiency. The

final inspection

was done by “women experts who apply every test of practical sewing to each machine”.

For the next few years, business was booming ,

including good export sales all over the world. In 1906,

Steven A Davis

returned as

factory superintendent after a 5 year absence. I am very curious why he left for those 5 years. A dispute with

the new owners, maybe?

For the next few years, business was booming ,

including good export sales all over the world. In 1906,

Steven A Davis

returned as

factory superintendent after a 5 year absence. I am very curious why he left for those 5 years. A dispute with

the new owners, maybe?

In 1909, a dealer in Springfield, MA did a special display of New Domestic machines and had three attached to

electric motors, which attracted a lot

of of attention. This is the first reference I found to electrifying Domestic machines.

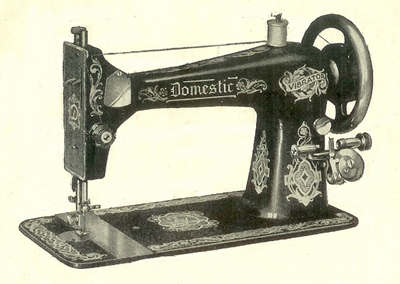

The Domestic D

was introduced in September of 1909 as the new flagship model, with 6 new patents granted or pending.

The advertised it as being "Distinctly "Old Domestic" in Principle", which seems kind of odd considering their previous

leading model was called the New Domestic.

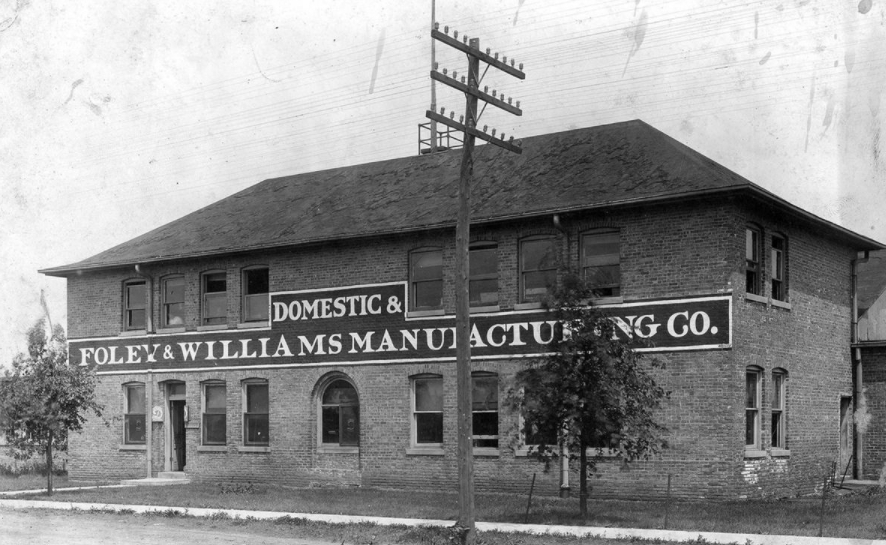

1910-1915 The Foley and Williams Years (Chicago)

In 1910, the Domestic Sewing Machine Company borrowed large sums of money from Kidder, Peabody & Co, bankers in Boston.

The bank placed

Herman Huke

in an executive position with the DSMCo. Huke

decided to sell the company to Foley and Williams, Inc. of Illinois. This sale included the trade

name, goodwill, trade marks, patent rights, and all property of the DSMCo as well as all stock, except for

stores and property in NY reserved for Benjamin Crass.

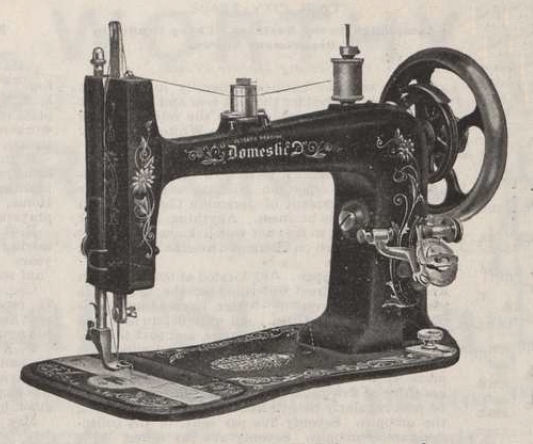

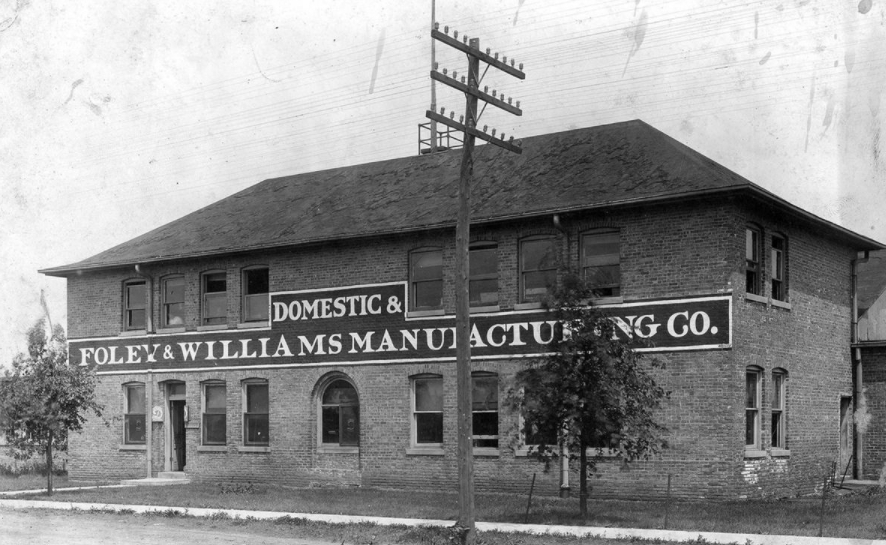

image source

image source

Foley and Williams promptly incorporated the

Domestic Sewing Machine Company of Maine.

This was not widely announced in the press. The announcement in the

Sewing Machine Times

merely stated that the company was

transferring their machinery, stock, sewing machines and sewing machine business to the DSMCo, Chicago with

large factories in Kankakee, Ill where Domestic sewing machines would thereafter be manufactured.

There was no mention of Foley &

Williams. This was very different than the Domestic financial troubles in 1873 and 1893, which were widely

reported in newspapers across the country.

Superintendent Davis, foremen and skilled workers were transferred to Kankakee. The company also discontinued

retail stores that had been opened in several large cities in recent years, allowing them to be taken over by

their managers.

There was another article that stated two companies closely identified with the interests of DMSco, the Standard

and Progressive Manufacturing Companies needed more manufacturing space and formed the Eagle Company and purchased

and moved into the Newark factory.

The Chicago location was stated to be advantageous for shorter supply and distribution lines. A good stock of

machines on hand was expected to prevent shortages during the move. Production likely moved into existing F&W

factories, but a

new Domestic factory

was also built, described in June 1910 as “a mammoth affair that will give

employment to hundreds of men.” In October, with the work of installing the business in the new factories

completed, Steven A Davis retired.

The Chicago location was stated to be advantageous for shorter supply and distribution lines. A good stock of

machines on hand was expected to prevent shortages during the move. Production likely moved into existing F&W

factories, but a

new Domestic factory

was also built, described in June 1910 as “a mammoth affair that will give

employment to hundreds of men.” In October, with the work of installing the business in the new factories

completed, Steven A Davis retired.

In May, 1911, Benjamin Crass made a deal with

Gimbels

to sell DSMs. This was important enough for President

Foley of DSMCo to travel to NY to consult in the deal. Later that year, Crass made a similar arrangement with Gimbels

in Philadelphia, which was believed to be the largest dept store retailer of sewing machines.

In 1911, Domestic began making the Franklin VS sewing machine for Sears. In 1913 , they replaced Davis as the

manufacturer of the Minnesota A and introduced their first rotary machine.

June 1913, Foley & Williams and several other manufacturers protested the removal of the

tariff

on sewing

machines. The tariff was removed, and

this article

stated that it became cheaper to buy sewing machine heads

and mechanical parts in Germany and assemble them at the Kankakee plant at 2/3 the cost of manufacturing

the entire machine in house. W. C. Foley contracted with German companies and laid off most of the Kankakee

workers. The World War I broke out and the German contracts fell through, resulting in the company going bankrupt.

Whatever the cause, in October of 1914, it was announced that DSMCo was again being placed in the hands of a receiver.

1915-1923 The King/Sears Years (Buffalo)

Trustee Len Small conveyed

property and assets to Harris Brothers Company of Chicago.

In May of 1915, Harris Brothers conveyed all assets to

Sears Roebuck & Company

of NY. This included the 15 acre factory property in Kankakee and the good will and trade name of the Domestic

Sewing Machine Company.

The Kankakee factory contents were

auctioned off on July 14, 1915. The auction ad listed the Good Wills and

trade names of Foley and Williams and mentions several of their models. Domestic Good Wills and trade names

were not listed because they had already been sold to Sears. The auction included the "models, dies, jigs,

fixtures and patterns of the Domestic Sewing Machine Company". This indicates that the new owners had no plans

to continue manufacturing the current Domestic models, but what about the Franklin and Minnesota A?

In December of 1915. Sears Roebuck created the

Domestic Sewing Machine Company of New York. They

moved Domestic manufacturing into the King factory in Buffalo.

Click here for information about the King Sewing

Machine Company and their connection to Domestic and Sears.

Similar to when Foley & Williams bought Domestic, there was virtually no press coverage that I can find when

Sears bought Domestic.

Several new King, Domestic and Sears branded models were introduced in the next few years, which will be

covered in detail on the Domestic Models and Dating pages (coming soon!).

In 1923 or 1924, White bought Domestic. Katie Farmer reported that White company records say it happened in 1923.

The first White made

Domestic Rotary was introduced in late 1924, which fits the timeline for a 1923 ownership change. This

investment ad from 1926 says the

White Sewing Machine Company contracted with Sears to buy the Domestic SMCo and parts of the King SMCo in 1924 and

the consolidation happened in January of 1925. This deal gave White the contract to produce all of the Sears

sewing machines until 1935.

I refer the reader to Katie Farmer’s White Sewing Machine Research Project for information about Domestic

after that time.

Company Headquarters and Factory Locations

As you have read, the DSMCo chaned business names, headquarters and factory locations a number of times over

the years. Click

here of a chart showing a summary of those changes, plus some information about the factory locations.

Miscellaneous Interesting Tidbits That Don’t Fit Anywhere Else

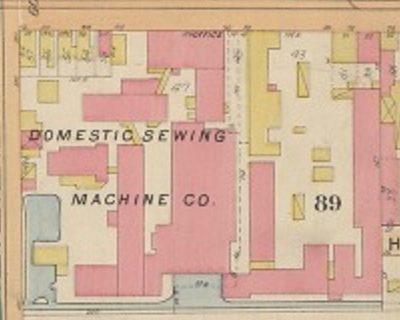

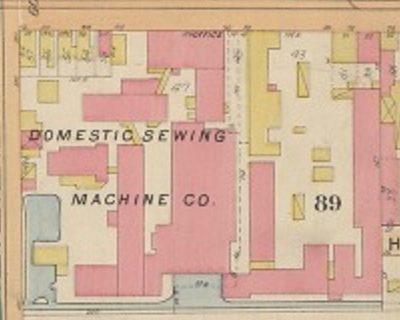

The Domestic factory in Newark was located at 98 Warren Street. This 1901 map shop shows the numerous buildings and that

it was located on the

Morris Canal. Canal plane #12 was directly behind the factory. This

undated photo

shows Canal plane #12.

The Morris Canal was originally built

primarily to haul coal, and largely fell out of use with the expansion of railroads after the Civil War and was

obsolete by the early 1900s, so was probably not used for shipping of sewing machines.

Image source:

Newark Public Library Click

here for larger image

DSMCo employed 2

blind seamstresses , Misses Cecelia and

Bernandina, who had been trained at the New York

Institution for the Blind. The two women were quite expert with most of the attachments and did demonstrations

at fairs and art exhibits all around the country for about a decade beginning in 1874. Cecelia was at the

Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 and hundreds of thousands of visitors saw her work.

In 1873, the

balloon for an attempted transatlantic balloon flight was sewn by 12 seamstresses using Domestic

machines in the new Domestic Building. The balloon was said to be constructed of about 8 miles of seams in

over 4000 yards of fabric. This is an account of the flight, which was one of 17 unsuccessful transatlantic

balloon flights. The first successful flight did not happen until 1978!

This is an account of the flight.

In 1873, a crowd gathered on the sidewalk to watch as a

carrier pigeon named Ariel was released from the roof

of the Domestic building. The pigeon was expected to travel to Connecticut.

In 1892, Domestic ventured into the typewriter business with the

Williams Typewriter . It somehow marked

the letters on paper without a ribbon and was innovative in that the typed words could be viewed by the

typist. Other points of interest were ease of operation, perfection of work and durability. In 1894,

the sold the manufacturing tools for the typewriters to the Williams Typewriting Company. Ironically, the

Williams Manufacturing Company of Plattsburgh NY, makers of the New Williams and Helpmate sewing machines,

also manufactured

typewriters. Theirs was called "The Wellington".

In December of 1893, Domestic seamstresses using Domestic machines helped to sew dresses for

5000 dolls to

donate to children in New York City.

Domestic owned the National Sweeper Company.

William A Mack did very well financially from the sale of DSMCo to the Blakes. In 1872, he donated a

$2000 pipe organ to the Univeralist Church that he helped to found.

In 1875, Mack built one of the finest

homes in Norwalk, Ohio at 166 W. Main Street. The house had

modern innovations such as fire hoses in several locations and a burglar alarm.

Domestic did not buy Mason in 1916 as reported in Charles Law's book and on many websites. According to Katie Farmer

of the White Sewing Machine History Project, White began making Mason machines in 1903 after selling off Mason's

existing inventory. Domestic was never involved.

Questions Still to be Answered

Did William A Mack use the business name W A Mack & Co concurrently with Domestic Sewing Machine Company? Or was

W A Mack & Co just the Shoe Business?

If Singer was instrumental in forming the DSMCo, why are they not mentioned in the complany history in any

of the lawsuits, or apparently in any other references? Does anyone have more information about this?

When exactly did the Blakes take over DSMCo? Why do documents talk about incorporation in 1870

when papers were clearly filed in December, 1868? There may be some period of time after filing the

certificate of incorporation for paperwork to get processed, but I can only see that going into early 1869,

not for 2 years. Does anyone know how to look this up in historical records?

I searched the business database on the Ohio Secretary of State website and did not find anything.

Why did Domestic buy Grover and Baker?

The articles about Domestic moving from Newark to Kanakakee mention other Domestic plants in Torrington, CT,

and Marion, IN. I have also seen fires at factories in New York City mentioned in a forum. Can anyone provide

documentation of any of these factories? Up until the move from Newark to Kankakee, articles made it sound like

all of their manufacturing since 1873 took place in Newark.

References

If you clicked on the reference links, you saw that most of my references were news accounts. As we know, newspapers

are not always entirely accurate, especially when they are reporting plans vs. events that happened. However, my opinion

is that most contemporary news accounts are probably more accurate

than historical summaries and reminiscences written years later. I marked the news clips

with their publication date. I marked

Sewing Machine Times articles SMT plus the date. Some of the SMT articles are from years after the events, so I

did not trust that information as much as contemporary articles when information such as dates did not match.

I consider the court records from lawsuits to be my

most accurate sources since they contain sworn testimony and documentation,

but even they contain some vague

details on events far in the past. If you want to read these lawsuits, here are the links:

Acknowledgments

I want to thank all to the collectors who have sent me information, photos and documentation of their machines,

filled out my surveys, and generally been helpful and encouraging about this project over the years. Special thanks to

Jon H, who has an eagle eye for ads, articles and sales listings containing important information, and who

introduced me to the Sewing machine Times.

Jim S, who pointed me to the New York Supreme Court case that answered so many questions.

Katie Farmer, with whom I have had many email communications over the years as we discussed the connections between

Domestic and White and the machines that were made by both companies..

William A Mack

began manufacturing parts for sewing machines in Seville, Ohio in

1860 .

William A Mack

began manufacturing parts for sewing machines in Seville, Ohio in

1860 .

By March of 1871, the company headquarters had moved to

By March of 1871, the company headquarters had moved to  The Blakes moved the company headquarters from Toledo to 96 Chambers Street in New York, NY and proceeded to build a

grandiose building to house the company. They chose the site of the

The Blakes moved the company headquarters from Toledo to 96 Chambers Street in New York, NY and proceeded to build a

grandiose building to house the company. They chose the site of the

In 1880, the Newark factory was

In 1880, the Newark factory was

On May 19, 1893, two

On May 19, 1893, two  The new management promptly began

The new management promptly began

For the next few years, business was

For the next few years, business was

The Chicago location was stated to be advantageous for shorter supply and distribution lines. A good stock of

machines on hand was expected to prevent shortages during the move. Production likely moved into existing F&W

factories, but a

The Chicago location was stated to be advantageous for shorter supply and distribution lines. A good stock of

machines on hand was expected to prevent shortages during the move. Production likely moved into existing F&W

factories, but a